The first level of Terra Nil feels like perfection. What you give to the land and what you take from it renew each other, and so tasked with restoring a barren quarry to a thriving ecosystem, you start small. Far from the city builder convention of widely mapping out your infrastructure, you attend to small patches of land – one wind turbine and a handful of toxin scrubbers to clean the earth at a time, paid for by the irrigators you place to restore the grass on top of it.

With a foundation set, the next task is to restore local biomes, of wetland, forest and fynbos. There’s something tactile and immediately satisfying about converting one of your irrigators into a hydroponium and seeing it ripple out into wetlands, or placing a beehive and hearing the brush of flower and scrubland pop up.

At the same time, it’s made clear that you aren’t freely zoning the land like an architect, or even a gardener. There’s a moment when I start a controlled burn when I expect it to only take the flowers I targeted – only for the fire to rip through to the natural boundaries of cliffsides and water edges. And while I’m able to put down the machinery that raises the humidity to bring back rainstorms (and salmon, and mosses), the rain by itself does a better job of cleaning up than I did.

When the biomes are in balance, and native animals returned to their ideal habitats, it’s time to recycle everything, leaving only a self-sustaining ecosystem behind. It’s easy for me not to see the whole picture before this point, as I focus on patches of hills, lowlands and small clusters of buildings, and cleaning up afterwards becomes an emerging ‘reveal’ of everything I’ve worked on. And there’s an option to “Appreciate” it before moving on to the next level, where the camera gently pans over the new landscape.

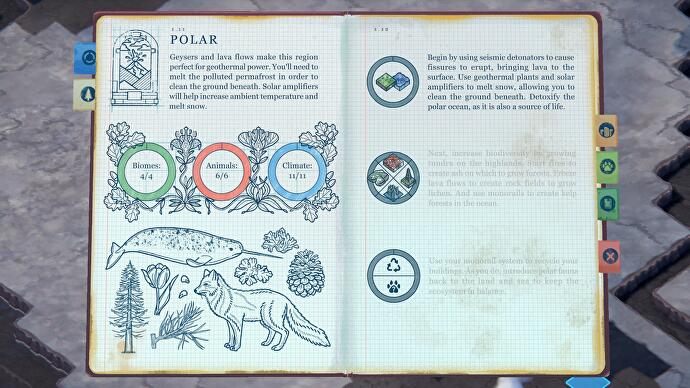

The balance between the first region’s relaxing atmosphere and smooth, thoughtful progression sets a high bar for the following stages – which, as they expand in complexity and difficulty, trade that smoothness for experimentation. There are four regions in total, plus unlockable endgame maps, and each come with their own unique visuals, mechanics and challenges.

There’s a significant bump in lateral thinking required, and while I wouldn’t call Terra Nil a difficult game, later stages hold a more ‘puzzle’-shaped space, where it’s possible to find the wrong solution first. I was surprised to find myself needing to restart phases – and sometimes the entire map – because I’d backed myself into a corner. I could clean soil, or place biomes, but not enough to pass a given stage – or I just straight ran out of resources, although that can be turned off in ‘zen mode’. While unexpected, getting to play detective, and the ensuing ‘aha‘ moments, more than make up for it.

The scope of lateral thinking increases significantly, as biomes have their prerequisites – and their prerequisites can have prerequisites. So maybe the humidity is too low to place a particular building, but placing cloud seeders around my natural water sources won’t make enough of an impact. I can channel out more, or create tiny ocean islands to build on – but either run the risk of reducing the land availability for other biomes, and it may always turn out that raising the humidity now creates issues for placing a different building later. It’s a delicate ecosystem, and a network of problem-solving.

Each region’s new mechanics do allow for their own moments of wonderful satisfaction. In the polar region, for instance, you start off excavating fissures of hot lava – which raises the ambient temperature as a side effect. When it gets to above zero, all the snow on the map melts, revealing previously inaccessible earth. At a later stage, you have to convert that lava to rock, which cools the temperature… and with the right humidity and toxicity, fresh snow begins falling again, cleaning the seawater and any remaining exposed earth. Incidental, emergent moments like these happen across each map, and they’re always striking.

These moments of wonder do balance out with some less fluid experiences. For example, many of your biome buildings are recycled from your irrigators or toxin scrubbers. But when the UI encourages you to place these sparingly to start with, it chafes to just put down new, wasteful, orange-tiles-of-inefficiency ones solely to recycle them – like I’m someone who just discovered upcycled pallet furniture, and goes to buy new wooden pallets off eBay.

It can also get excessively click-y in some places, such as with the monorail system, which transports goods from land to ocean, and also recycles its immediate surroundings. Building a monorail network to recycle every building on the map, and then issuing the instruction to recycle 20 or 30 nodes individually (in order, so you don’t break the network) made me glad to have an ergonomic mouse, to say the least.

With so much of its design oriented around environmentalism, I have one significant bugbear with Terra Nil: in the context of the entire game, the absence of humans moves from ambiguous to conspicuous. It’s made clear that the setting is post-climate disaster, and the narrative is explicit that there is nowhere for you on the entire planet. Your exit is the happy ending for each level. When so much of its gameplay revolves around sustainability – renewable growth, and not taking more than can be given – it feels dissonant, as well as fatalistic, to imagine that only possible within an ecosystem where all the humans are gone.

Even where Terra Nil makes choices I don’t always enjoy, I enjoy that it does make these novel, ambitious choices. More than simply the gentle vibes it seems to suggest on the surface, Terra Nil offers engaging puzzles, a thorough commitment to what an environmental city builder could look like, and lingering moments of actual perfection.