I hope you don’t mind if I get a little frank with you here. I’ve struggled to write this piece on Shadows of Doubt for several days. Not because I don’t know what to say – I know what I did and didn’t like during my time exploring several different generated cities – but because I’m not sure how to string together my thoughts on this game. And I think the reason why I’ve found it so hard is because I’m not sure Shadows of Doubt itself knows entirely what it wants to be.

We’ve previously written about Shadows of Doubt before. Martin covered the game for Rezzed Digital in 2020 and I read through his thoughts before I started playing. He was impressed by what he saw, and I know Martin’s a good egg, which made me excited to try it for myself. The various descriptors which have been given to Shadows of Doubt had me scratching my head though. Martin called it “a first-person detective stealth game set in a procedurally-generated noirish city”, while developer Cole Jefferies also describes it as sci-fi noir and an immersive sim.

It’s certainly a detective game. The game doesn’t hold your hand while you solve cases. It’s up to you to collect evidence and figure out who the culprit is. The in-game pinboard where all your evidence hangs will automatically create connections between linked items. It also allows you to make your own notes and connections between bits and bobs, a physical space in-game to help you make sense of the crime.

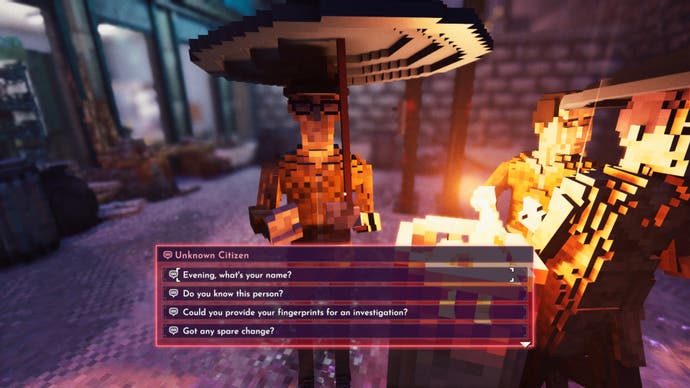

There’s a wonderful freedom to your approach in solving cases. If you need to search a location, you can try and sneak in either by picking the lock or climbing through vents. You can break in, after a series of increasingly loud knocks. If someone’s inside, you can try bribing them. Most citizens aren’t willing to open up that easily, so you often have to resort to one of these methods to find what you need. Frustratingly, you can only ask a specific set of questions. Unlike Ace Attorney, where you can present evidence and see what sort of response you get, I was disappointed that I couldn’t ask people about specific pieces of evidence, such as proof of a phone call.

Outside of solving cases, I found it extremely fun to explore the world. Even in the smallest city size, there’s plenty of buildings to nosy around – after letting go of my reluctance to break the law (consequences be damned!). I really enjoyed breaking into apartments and offices and snooping about, looking in fridges and seeing if there’s anything to eat, stealing any money left lying around, and hacking into computers to read emails and employee profiles.

I love this gameplay loop, but at the same time I rarely felt engaged with it. Everything within the world feels formulaic, and perhaps this is the trade-off with procedural generation. Citizens respond to questions with the same answers. Homes rarely feel personal, often decorated with a TV and shelves of assorted books. Snooping into emails, what should be the most personal of communications in this setting, simply brings up the same messages, just addressed to and from different names.

There’s little consequence to the world or your actions in it. I was spotted trespassing and stealing within an apartment block, and was actually being chased by security guards, but once I ran out of the building and lost my pursuers, nothing changed. I could re-enter the building Scot-free and no one remembered the chaos from a minute ago.

Likewise, your approach to solving cases has no effect on the outcomes. So long as you get the details of the crime correct, such as the name of the perpetrator and what evidence places them at the scene of the crime, you get your payment for a job well done and your social status increases a bit. It doesn’t matter that I stole money from the perpetrator’s wallet, or that I repeatedly knocked out a witness to my trespassing and thieving as I searched my suspect’s apartment.

Perhaps this is the trade-off for a noir setting – a grim world where crime is rife and the law exists only in the hands of the people. But, and this is clear even at a first glance at the game, Shadows of Doubt takes more cues from cyberpunk than noir and sci-fi. The game takes place at the turn of 1979, in an alternate universe “where hyper-industrialisation has swept the planet”. Corporations struggle for power while a new state, the United Atlantic States, has elected the megacorporation Starch Kola as its president.

The UAS is a “loose” group of Western Europe and North America countries, firmly placing us within the western part of the world. But every generated city has the same Asian iconography perpetuated in cyberpunk. Neon lights. Random jumbles of Japanese, Chinese and Korean writing put together on signs. Paper lanterns line some streets, while others randomly have Chinatown arches placed there. As I walk around the different cities the game has generated, all I can think is: why? Why do these all exist here? Why is there nothing stereotypically French or Italian lining the streets?

While I haven’t been able to stomach this long enough to find out about the origin of Starch Kola in-game, or even if its origin is explained, one loading screen tells you about a technology corporation called Kaizen-6, which was founded by someone called Kyra Cho. Kaizen-6, with its Japanese name, founded by someone with a common Korean surname. The more you look, the more you see it. The conflation of East Asian countries into one “entity” as a representative of American techno-orientalism is nothing new within cyberpunk or video games, but I’m sorely tired of it.

Likewise, as you start to inspect the finer details of the world it all starts to make less sense. Physical letters are transmitted around the city using vacuum tubes, only to then be electronically displayed on a computer (or micro cruncher, in the game’s slang). In one of my cities, a murder was committed by, as I found out using the local government’s citizen database, a contract killer. Their occupation was written in the database as contract killer, but if the government already knew this then why had this person not already been arrested?

On paper, I should be absolutely enamoured with Shadows of Doubt. Immersive sim? Check. Detective? Check. Noir? Check. But despite a fun gameplay loop, none of its parts seem to click together well. I’m not sure if procedural generation can capture what makes an immersive sim or a detective game good – a place where consequences have a true impact and the characters which live in it feel like fully fleshed individuals. I will admit, it’s an impressive piece of engineering – the sheer amount of objects and information which the game has to generate and interweave connections between is fascinating. But for a game with so much literal substance to it, it felt ironically reductive in its experience.